EIA’s projections for individual shale gas plays

My news feature in the Dec. 4 issue of Nature, “The Fracking Fallacy,” centers around recent forecasts from a team at the University of Texas, Austin (UT), which has done arguably the most comprehensive studies of shale gas plays—at least, of any study that’s been publicly released. The UT forecasts are significantly below those by the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) as well as most industry analysts.

The Texas team’s results are “bad news,” said Tad Patzek, head of UT's Department of Petroleum and Geosystems Engineering, and a member of the research team. If the U.S. continues trying to extract gas as fast as it can, and tries to export large quantities overseas, he said, “We’re setting ourselves up for a major fiasco.”

For the bigger picture, check out my Nature article. In this post, I’ll delve into detail on the U.S. government’s forecasts for shale gas. In future posts I’ll cover the Texas team’s work.

EIA’s forecasts

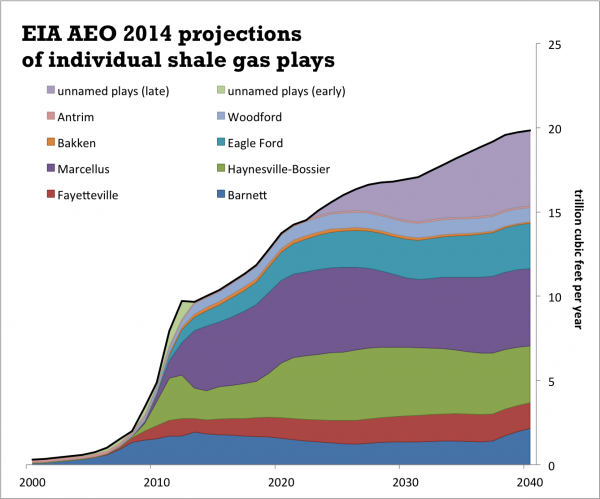

Here I’ll show the forecasts first, then explain more about them. First is production from all the plays summed up:

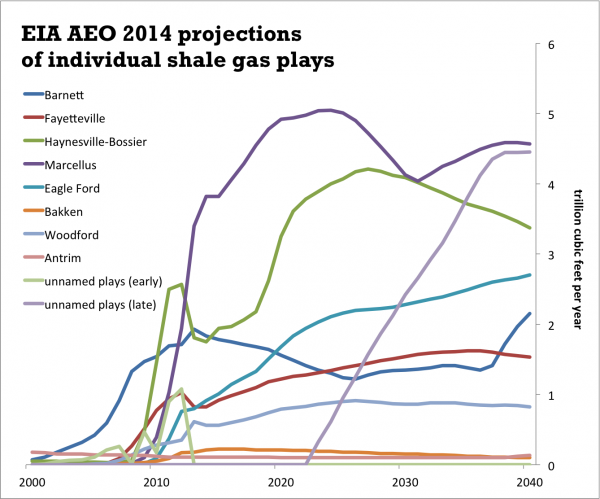

Here is each individual play separated out, to give a clearer sense of their relative scale, and to show how some plays' production is expected to plateau.

If you want the underlying data, it’s posted on Github.

The backstory

Last spring, when I started gathering material for this Nature article, I wondered whether the EIA made forecasts for individual shale gas plays, since they’d shown forecasts for individual tight oil plays in AEO 2013. The EIA hasn’t released their projections for individual shale gas plays, but I asked one of their analysts for the data, and they gave me the spreadsheets. EIA had never published these, as far as I’d seen, and at the time I asked for the data, I hadn't seen it in any reports or papers. (When I showed these to a couple of analysts at a non-profit, they were surprised, and said, “How did you get these?” I told them, “I just asked for them.” Which goes to show, it never hurts to ask.)

- EIA calls their numbers for future production “projections,” and insists they aren’t forecasts, because they make a range of projections for some thirty-odd different cases, the main one being the “reference case.” But if you look up the word “projection,” a typical definition is “an estimate or forecast of a future situation.” Also, their “projections” are in a section of their website with the URL www.eia.gov/forecasts/…. I pointed this out to them a few years ago, and they said it was unfortunate and they should change it—but they haven’t. Even if they were consistent about calling them “projections,” though, I still maintain that they are forecasts—it’s just that they issue a range of forecasts, based on varying assumptions. More importantly, most everyone would still think of them as forecasts.

The shale gas forecasts I got from EIA listed 8 individual plays—but in a number of years, total shale gas production they forecast was somewhat larger than what these named plays contributed. So I added in two categories for the contributions from these unnamed plays—"unnamed plays (early)" for the contributions from 2000-2012, and “unnamed plays (late)” for 2023-2040. (Oddly, in the years 2013-2022, the sum of forecast shale gas production from all the named plays is very slightly more than the total of shale gas production that EIA shows. I ignored this discrepancy; it was just a few percent of the total.)