How the shale gas "revolution" stacks up

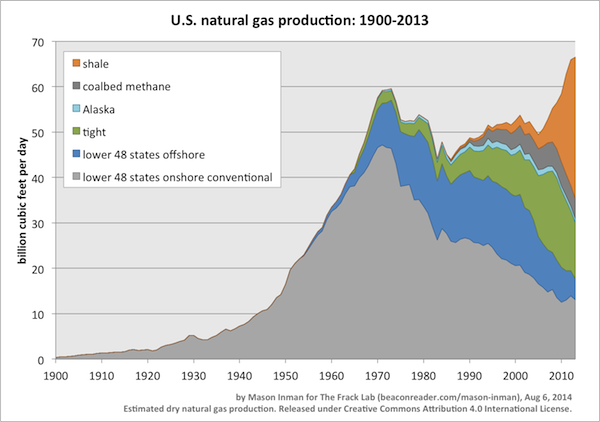

It’s surprisingly difficult to find a long-term picture of U.S. natural gas production, which separates out the various sources of gas, and also gives the underlying data. So here I've cobbled together data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) and various other reputable sources.[1]

This isn’t meant to be a replacement for official data. It’s just to show a close approximation of where the United States’ gas has come from over its entire history. To download the underlying data, see this Github page. For the data sources, see this Github wiki.

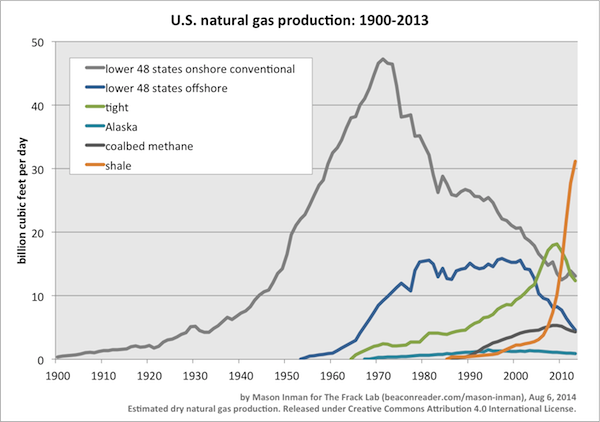

Here’s another look at the data above, but instead of stacking up each type to sum to a total, it shows each type on its own.

This shows how the nation has burned through one source, and when it got increasingly difficult to raise production, it then went after another source—each increasingly difficult to access or extract.

Production from each source has gone through its own boom: Conventional gas extraction soared through the 1960s. In the mid-1960s through the 1970s, offshore gas scaled up. Then in the 1980s and 1990s came tight gas. But for each source, after the boom, whether long or short, came a decline.

Even with the addition of new sources of natural gas requiring ever-more-complex technologies—including deepwater offshore drilling rigs, fracking and acidization to open up tight gas formations, or drawing on coalbed methane and gas fields in remote Alaska—these sources didn’t look like they’d be able to keep U.S. production up. The 1990s also saw the scale-up of coalbed methane.

But none of these were enough, it seemed, to keep U.S. natural gas production flat, let alone boost it higher.

A decade ago, the outlook was dire. Testifying to Congress in 2004, Daniel Yergin—an energy historian and analyst, then chairman of the consultancy Cambridge Energy Research Associates (CERA)—was deeply worried about the future of U.S. natural gas. Yergin warned of an approaching “gas supply crunch,” saying in his prepared testimony: "in spite of industry efforts, which will yield very strong spending and drilling efforts for the foreseeable future, North American natural gas productive capacity is not expected to grow meaningfully, and United States gas productive capacity appears now to be in permanent decline."

CERA had completed a report “Can We Drill Our Way Out of the Supply Shortage?” Its conclusion, as Yergin put it: “There is strong evidence that simply adding more drilling rigs will not solve the problem, as it has in previous decades.” (Link to pdf of Yergin’s testimony.)

He was right about that. Rather than simply adding more rigs, it required a change in the use of technologies: a combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing (aka fracking), tuned through trial-and-error to make them work in particular shale gas formations, first the Barnett in Texas, then other formations across the country.

Once drillers figured out how to use fracking to reliably get large amounts of gas out of shale, this kicked off the “shale revolution” of the 2000s. The boom has seemingly produced as many superlatives as it has oil and gas, with words like “game-changer” and “disruptive,” “transformative” and “renaissance” all becoming part of the parlance of our times. Yergin abandoned his gloomy view of “permanent decline,” and is now a great optimist about U.S. natural gas, speaking of a “shale gale.” As the Economist put it, “The shale-gas revolution in America has been as sudden and startling as a supertanker performing a handbrake turn.”

For better or worse, this turnaround in production—and in attitudes—is all due to shale. As Yergin argued a decade ago, none of the other sources seemed capable of coming to rescue—and since then, nothing much has changed about the outlook for those other sources.

So the future of U.S. production depends hugely on how shale gas fares over the long term.

In my posts on The Frack Lab (a project on Beacon Reader), I’ll take a critical look at shale gas and oil production, to see how much of the “shale gale” is actually hot air.

Some former shale boosters have broken ranks to argue the usual industry hype has gone too far. In August 2013, Peter Voser, then CEO of Royal Dutch Shell, called the notion of a worldwide shale revolution “a little bit overhyped.” (Whenever I hear the word “overhyped,” it always makes me wonder: What’s the right amount of hype?)

And in late 2013, the International Energy Agency’s chief economist, Fatih Birol, back-pedaled from the Agency’s earlier excitement about shale, insisting it be called “a surge, rather than revolution.”

Shale has undoubtedly been a boom. But will it continue booming for decades? Or will it go bust?

References:

- ↑ This article is re-posted from The Frack Lab https://www.beaconreader.com/mason-inman/how-the-shale-gas-revolution-stacks-up